Fashion and the Sustainable Future

The two chapters “Mauve Mania” and “Dyeing the Cloth” discuss how textile industries have long used natural materials to dye cloth before new innovations and industrialization presented a wide range of cost-effective and colorfast options. With a rising international synthetic dye market, style industries began struggling with the new surplus of colors. Textile designers had to keep up with quickly changing mass market fashion trends, in which artistic originality was replaced by the ability to develop exciting and innovative uses for popular colors. In a TED Talk from 2017, the founder of Faber Futures, Natsai Audrey Chieza, presents an approach aimed at integrating the worlds of design and synthetic biology. Using synthetic biology to redefine our material future, her project aspires to dramatically reduce pollution in the fashion industry by replacing unsustainable industrial processes with natural alternatives. She is currently focused on introducing the world of fashion and technology to the bacteria Streptomyces coelicolor: soil-dwelling organisms that, in interaction with protein fibers, produce a pigment which ranges in colors from blue to pink to purple. This pigment creates colorfast textile dyes without the use of chemicals and with less water usage than traditional processes. She is painting a future, in which the fashion industry could become a leader in sustainability.

Chieza, Natsai Audrey, TED Talk

- Most of the ecological harm, caused by textile processing, occurs at the finishing and the dyeing stage. … (05:30 – 06:06)

- And you can see, how this process generates very little runoff and produces a colorfast pigment without the use of any chemicals. (06:55 – 07:32)

- If we can do this, then we can move what happens on a petri dish so that it can meet the human scale, and then hopefully the architecture of our environments. (08:46 – 08:59)

- I am working to see how their platform for scaling biology interfaces with my artisanal methods of designing with bacteria for textiles. (09:51 – 10:22)

- Here is the exciting thing: I am not alone, there are others who are building capacity in this field. … (10:44 – 11:26)

Blasczyk, Lee, “Mauve Mania” In The Color Revolution

- The manner in which colorists and chemists approached the dye research was guided by the market. … (p.27)

- Most important, the focus of research shifted from industrial engineering and the improvement of processed and products to the discovery of new colors. (p. 29)

- Every generation discovers new needs and re-invents practices for current circumstances … . (p. 31)

Waldbauer, Gilbert, “Dyeing the Cloth” In Fireflies, Honey, and Silk

- … the value of cochineal produced during those centuries exceeded that all of the gold and silver that the Spanish stole from the native inhabitants of the New World. (p. 53)

- … the cochineal dyes are – unlike synthetic dyes – virtually permanent, because they resist fading from light and washing. (p. 61)

- Following the invention of the first synthetic dye in 1856 – soon followed by the synthesis of many others – the international market for cochineal and other natural dyes rapidly collapsed. (p.63)

fur skin sustainability

Most natural fur products come from the four fur auction companies: Kopenhagen Fur, North American Fur Auctions (NAFA), American Legend Cooperative, and Saga Furs. Other than fur trade, fur classifications and certification are among their main tasks.

Environment: natural fur vs. artificial fur, biodegradability and compostability, pollution from production.

(Life Cycle Analysis (LCA), prepared by DSS Management Consultants Inc. at the request of the International Fur Federation, is aimed to demonstrate that real fur is better for the environment than artificial fur.)

Animal welfare: see the case of Danish mink farms (video). Not all the farms have the same condition as that in the video.

Globalization: In the East, fur trade and production haven’t been fully regulated, although organizations in China and Russia have made a lot of progress in recent years, but those countries need more governmental regulations and university researches on animal welfare, leather production, dyeing, etc.

Bio-leather: fibers from ”kombucha”!

Advantages: organic, vegan, easy dyeing, less water

Disadvantage: soggy in rain (so it’s not ready for the public yet.)

Sana’s Blog post

Yes, Fashion is Racist

I apologize for this not being up sooner, I know that on the first day of class, Wissinger said Wednesday morning, and it is that, I like to be even earlier. Alas, a boiler in my building caught fire on Sunday, so I’m just now back at home.

Zara says this shirt was inspired from “classic American Western” tradition, and that the star was a sheriff’s badge. Because, when I am thinking of a sheriff, I am definitely thinking about someone wearing prison stripes. In clothing easily pulled off over the head.

Zara immediately took it down, but this wasn’t the first instance of anti-semitism from the brand. In 2007, they printed a handbag with four green swastikas embroidered about the face of it, and were forced to recall that bag as well. In that instance, they noted that the swastika is a symbol for peace in Sanskrit, and was a beloved symbol of the Indian people before Hitler coopted its use.

However, Hitler coopted its use more than 75 years before Zara released the bag, so it raises the question, how did both of these items pass the multiple layers of management to hit the sales racks? The answer seems pretty clear, at least to me.

Is Fashion Racist?

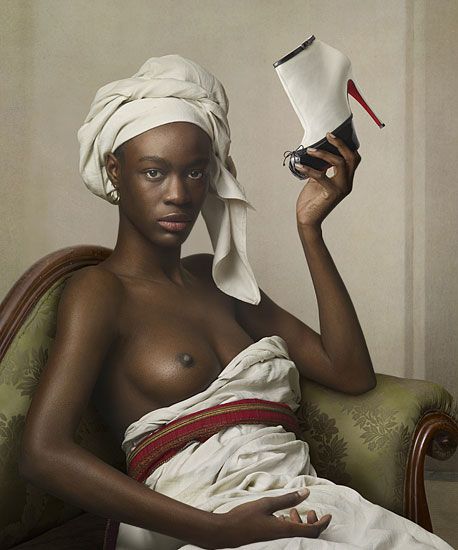

Marie-Guillemine Benoist (December 18, 1768 – October 8, 1826) was a French painter, who was classified at the time as a ‘feminist’ painter, having previously made paintings such as Psyché faisant ses adieux à sa famille which was considered a feminist painting, as the vice figure (the vice is known as a figure committing a sin) was a man and not a woman.

In 1800, six years after slavery had been abolished, she created the piece Portrait d’une négresse. This painting was later brought by Louis XVIII. According to sources, this painting was supposed to become a symbol of black women’s rights and female empowerment. It would be discovered much later that this woman in the picture had no choice in how she was portrayed in the picture, despite even being a part of Benoit’s family.

In the Louboutin ad we can see history repeat itself, and whether or not Louboutin or the marketing team knew the implications or past of the original painting is up for debate. However, the context is almost the same; although they had good intentions behind it, it was still a very naïve way of not just the very perception of the black woman, but the portrayal of it is still horrifyingly adolescent.

Isn’t feminism supposed to embrace all cultures, and not be biased as the advertisements were? Absolutely. Rihanna’s Fenty collection has already been making waves for celebrating black beauty with her Fenty Cameo collection. And hopefully, in the future, today’s advertisements could decently portray the black woman of the past and the future.

Fashion and Otherness

The two paragraphs assigned “Re-Dressing Race and Gender: The Performance and Politics of Eldridge Cleaver’s Pants” and “To the Ends of the Earth: Fashion and Ethnicity in the Vogue Fashion Shoot” discuss how fashion and race affect one another. The Art Blake article about Eldridge Cleaver’s pants reflects on how the activist’s pants are a representation of Cleaver’s position on race and sex during the 1970s. “To the Ends of the Earth” by Sarah Cheang talks about the fashion industry using ‘exotic’ locations as a background for white models to assert the dominance of white people in places described as the ‘other.’ Race and fashion play off one another in these texts by examining how people who are non-white reject white society’s class and racial structures through fashion. However, even in cases where an ‘other’s’ culture is put at the forefront it is done in an exclusive manner. For example, Italian Vogue’s July 2008 all black issue was praised for being inclusive, but the fact that black models are perceived as outside of fashion and need their own separate issue rather than being included regularly speaks to the Eurocentric idea of mainstream fashion. Regarding gender, Eldridge Cleaver’s penis focused pants were not out of necessity for a high fashion black owned business, but to assert his manhood which he perceived as being stripped from him in traditional pants. To him, the ‘other’ were women and the fashion industry, which he felt did not cater to him. While one’s definition of who or what the ‘other’ is can change, fashion is used both by the oppressor and oppressed to rebel or assert one’s dominance.

“To the Ends of the Earth: Fashion and Ethnicity in the Vogue Fashion Shoot”

- “Body adornment plays a crucial role in the signaling and maintenance of social categories- it is a primary means by which we announce our belonging to particular ethnic groupings and also experience that belonging.” (36)

- “The concept of fashion that the Vogue title encapsulates is predicated on a series of interrelated ideas about modernity, cosmopolitanism and individual identity construction in an aspirational consumer culture.” (37)

- “In this fashion story, the model and her clothing have been decentered, both visually and through a range of supporting texts.” (41)

- “A highly internalized understanding of fashion as evolutionary- and the use of tribal cultures to comprehend Western society- explains the closeness between Walker’s visual repertoire and popular ethnographic forms of photography typified by the journal National Geographic.” (42)

- “Magazines are primarily spaces of consumption.” (43)

“Re-Dressing Race and Gender: The Performance and Politics of Eldridge Cleaver’s Pants”

- “Through literary and visual texts, Miller’s analysis of the black dandy and his place in American racial history provides a key conceptual frame through which to understand Cleaver’s interest in clothing and in dressing his gendered and racialized body at a point in his life when his political performance seemed to be losing an audience.” (14)

- “Mary Blume, a reporter with the International Herald Tribune, interviewed Cleaver in Paris on August 14, 1975.” (18)

- “Cleaver vociferously opposed the “unisex” look of the mid- and late-1970s” (21)

- “Let us return now to Les Halles, to the shop window in which Cleaver stood, posing, for René Burri.” (29)

- “Cleaver’s performance in Burri’s photographs, in the interviews he gave in France and the United States about his pants design, in his establishment of Eldridge Cleaver Unlimited, and in the photographs Nik Wheeler took of him and his merchandise in the California Mart and in his West Hollywood store should be understood as combining together into an autobiographical act.” (33)

Week 10 – Tansy Hoskins ‘Is Fashion Racist’

Tansy Hoskins piece “Is Fashion Racist” is an exploration on the many exclusionary practices within the fashion industry. Hoskins methodically analysis how different aspects of the fashion industry are systemically racist often through the guise of “Fashion” as something that is innately exclusionary. In Simmel’s Fashion (1957) he explains that “the very character of fashion demands that it should be exercised at one time only by a portion of the given group”(p. 547) Whereas the Fashion discourse has moved past Simmel in many way, there are strands of this concept that are still prevalent. These exclusionary practices manifest themselves through the lack of diversity when hiring of models, and then the lack of cultural sensitivity in advertisements and editorials. It also manifests itself in the appropriation of other cultures for the use of Fashion while at the same systemically hindering the growth of Fashion within non-Western countries. Despite this systemic racism, Fashion has a way of putting a veil over it, ignoring the racist, anti-Semitic, homophobic actions portrayed by designers, brands and magazines, highlighting the luxurious aspects and ignoring the discourse around the ugly.

Questions:

Tansy Hoskins “Is Fashion Racist”

- The production of fashion is a highly lucrative business. (p. 129)

- In August 2008 Vogue India ran a ‘Slum Dwellers’ shoot, …. (p. 132)

- It would be easy to reduce all fashion race-related stories … (p. 134)

- In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century cotton-weaving town like Manchester… (p. 135)

- Many feminists in 1968 could not understand why the black community … (p. 135)

- Beauty is a site for political resistance, though a problematic one. (p. 136)

- This merging of cultures could be taken as a sign of progress… (p. 138)

- Fashion’s penchant for imitating cultures reinforces the idea that cultures … (p. 139)

- The second response from the fashion industry is a strengthening of its racist … ( p142)

- Should artists be judged by their political beliefs? (p145)

Let’s Talk abut the Bard Fashion, Anxiety, and Labor discussion

Here is an article by panelist Minh Ha T. Pham that touches on some of the issues she mentioned last night.

If I did this correctly then you all can reply to this post and we can get access to your ideas and thoughts about what you learned last night while it is still fresh in your minds.

Repetitive Rebelliousness

SNL, 90th Oscars, Premiere of ‘Girls Trip”

https://www.cnbc.com/2018/03/05/why-tiffany-haddish-keeps-re-wearing-her-4000-oscar-gown.html

I chose this article to read alongside Llewellyn Negrin’s piece “Merleau-Ponty’s Theory of Embodied Existence,” and Jessica Kennedy and Megan Strickfaden’s piece “Entanglements of a Dress Named Lavern: Threads of Meaning between Humans and Things (and Things),” as a contrasting embodied experience. Merleau-Ponty, Kennedy, and Strickfaden speak about how the body and the thing modify each other. The audience can observe this symbolic alteration. In the article “Why Tiffany Haddish has worn her $4000 Oscar’s Dress at least 3 Times, ” Emmie Martin calculates that through amortizing, “Haddish has gotten the cost of the dress down to at least $1300 per wear” (Martin). Through repeated wear, Haddish changes the value of the dress. It is also necessary to note the dress’s own agency in its (his/her/their?) relationship to Haddish. The cost of the Alexander McQueen dress, impels Haddish to wear it more than once. The dress becomes synonymous with its value, which accrues additional value for Haddish because the dress cost more than her mortgage (Martin). We can observe the entanglement happening as Haddish’s personal life is woven into the very makeup of the dress. The mutual dependency between Haddish and the dress is further illustrated when this “breaking of social taboo” through the repetitive wear of the dress warrants explanation (Martin). Haddish must explain why she has decided to break the rules and wear an expensive gown more than once. She is almost forced to reveal how poverty and homelessness have influenced her decision to (re)wear this dress. Her body and dress are now entangled and influence how they navigate social and public spaces. The dress, in turn, is made famous (and Haddish too, made known for these rebellious actions), as the dress is “now iconic” (Martin). Speaking to the materiality of the dress, Haddish cares for it, and wears it despite its fragility and its whiteness is prone to staining. This expensive gown, is a very disposable thing. It is too delicate to be washed (only fabreezed), and too recognizable to be worn more than once. Haddish’s commitment to the care of the dress along with the way she and the dress imprint value on one another through repetitive wear point to the idea that,“when we act in the world, we do not act just as bodes, but as clothed bodies” (Negrin 130). We (and I include things in this we) always move dependently in spaces.