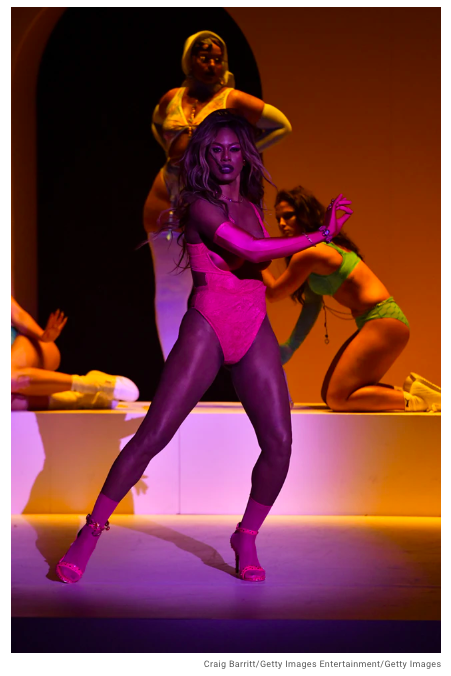

In Clothing Fit Issues For Trans People, Reilly, Catalpa and McGuire “surmise that transgender people will critique their ‘look’ based on their interaction between their apparel and their bodies in the context of social-constructs of gender presentation.” Looking at the Function, Expressive and Aesthetic Consumer Needs Model, and interviewing members of the trans community, they deduced that the RTW mass market was falling short in providing clothing that met the function and aesthetic, the fit and design needs of a trans person. I see Rihanna’s latest Savage x Fenty fashion show not as a fix to the problem but perhaps as a step in the right direction. Rihanna opens the show explaining that, “every woman deserves to feel sexy. We are sexy, we are multi-faceted and I want women to embrace that to the fullest.” These are not just words, but a value that she laid out in the casting of the show. The Savage x Fenty show showcased women of all different shapes, and sizes including notable women from the LGBTQ++ community, Richie Shazam (gender non-binary), Laverne Cox (trans woman), Isis King (born in the wrong body), and Acquaria (drag queen). Rihanna is showing the world that her line of lingerie is for everybody, that it has been designed using the functional-expressive-aesthetic model, functional pieces that fit a wide range of sizes and body shapes, expressive with their inclusive, self-loving, everyone is sexy messaging, and aesthetic, by positively influencing the way women embrace their bodies. NY Fashion Week is not new to male-to-female trans models, but what is progressive about the Savage x Fenty show, is that it is an affordable RTW lingerie line, it is not couture or a luxury brand where the fashion show is not realistic to what will be presented to the masses. When you look at the brands website, the diversity that was presented in the show is apparent, not only through the models, but through the wide range of styles and sizes offered at the retail level. The hope is that as Savage x Fenty, and other gender inclusive brands and companies, claim the spotlight that other brands and retailers see the need to consider trans women not only as models but as consumers, and that this realization will increase the options that we all have on the retail floor.